Workshop on Artificial Joint Intentionality (AJI):

Skilled Social Interactions in the Age of AI

DATE | ORGANIZERS | |

6–8 November 2025 | Cameron Buckner, University of Florida, US; Anna Strasser, DenkWerkstatt Berlin, Germany; Amber Ross, University of Florida, US; Duncan Purves, University of Florida, US; Kirk Ludwig, Bloomington, US |

This event is made possible through sponsorship by

the University of Florida Department of Philosophy, the UF Department of Sociology and Criminology & Law, the Donald F. Cronin Endowed Chair in the Humanities, the UF College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the UF Renwick Program for Ethical, Beneficial, and Safe Artificial Intelligence, and the Indiana University, Bloomington, Department of Philosophy.

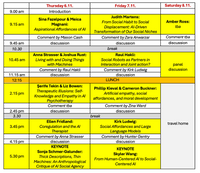

SCHEDULE

Times are Eastern Standard Time – EDT (Daylight Time ends 2.11.)

SPEAKERS & COMMENTATORS

* if you click on the names you will be guided to their website

Glenn and Deborah Renwick Leadership Professor in AI and Ethics at the University of Florida’s Department of Computer & Information Science & Engineering (CISE)

Sina Fazelpour | Anna Strasser | Joshua Rust | |

Serife Tekin | Liz Bowen | Ellen Fridland | |

Judith Martens | Raul Hakli | Cameron Buckner | Phillip Hintikka Kieval |

Kirk Ludwig | Amber Ross | ||

COMMENTATOR | COMMENTATOR | COMMENTATOR | COMMENTATOR |

Zina Ward | Mason Cash | Hunter Gentry | Zara Anwarzai |

KEYNOTE SPEAKER | |||

Sonja Schmer-Galunder

| Skyler Wang

|

ABSTRACTS

1. Sina Fazelpour & Meica Magnani: Aspirational Affordances of AI

As artificial intelligence (AI) systems increasingly permeate processes of cultural and epistemic production, there are growing concerns about how their outputs may confine individuals and groups to static or restricted narratives about who or what they could be. In this paper, we advance the discourse surrounding these concerns by making three contributions. First, we introduce the concept of aspirational affordance to describe how culturally shared interpretive resources, such as concepts, images, and narratives, can shape individual cognition, and in particular exercises practical imagination. We show how this concept provides a particularly useful for grounding evaluations of the risks of AI-enabled representations and narratives.

Second, we provide three reasons for scrutinizing of AI’s influence on aspirational affordances: AI’s influence is potentially more potent, but less public than traditional sources; AI’s influence is not simply incremental, but ecological, transforming the entire landscape of cultural and epistemic practices that traditionally shaped aspirational affordances; and AI’s influence is highly concentrated, with a few corporate-controlled systems mediating a growing portion of aspirational possibilities. Third, to advance such a scrutiny of AI’s influence, we introduce the concept of aspirational harm, which, in the context of AI systems, arises when AI-enabled aspirational affordances distort or diminish available interpretive resources in ways that undermine individuals’ ability to imagine relevant practical possibilities and alternative futures. Through three case studies, we illustrate how aspirational harms extend the existing discourse on AI-inflicted harms beyond representational and allocative harms, warranting separate attention. Through these conceptual resources and analyses, this paper advances understanding of the psychological and societal stakes of AI’s role in shaping individual and collective aspirations.

2. Anna Strasser & Joshua Rust: Living with and Doing Things with Machines

The progress made in generative AI (GenAI) may mark the beginning of a technological revolution. Artificial systems increasingly appear to be outgrowing their status as mere tools, encroaching ever more deeply into the domain of the social; they seem to overtake the role of alien collaborators in human-machine interactions (HMIs). However, because we assume that those systems are not like human social agents, we have difficulties describing them adequately. Analyzing an interesting aspect of interactions, namely how we choose from the infinite number of possible actions, we will use the framework of affordances to develop a nuanced understanding of the various types of interactions we can have with and without artificial systems.

In this paper, we (1) elaborate on a special feature of affordances by examining their functional role in facilitating the connection between perception and potential actions, (2) attempt to distinguish (mere) environmental affordances from social affordances, and (3) consider the extent to which the partners in HMIs can qualify as social affordances for each other.

In more detail, we begin our discussion of affordances by claiming that entities that qualify as an affordance for us seem to invite us to do something specific. Chairs invite us to sit, pens invite us to write, an out-reached hand invites us to shake hands, and even a threatening gesture may invite us to fight. Thereby, the space of potential actions we may choose from is reduced. And this results in an advantage as we often do not have the time consider the whole space of possible actions. Therefore, it is not surprising that research in computer vision has started to enable robots to take into account the affordances of objects and humans.

We go on to characterize the distinction between environmental and social affordances and pose the question of whether objects like artificial systems created with GenAI technology can only qualify as environmental affordances.

While the distinction between environmental and social affordances has been extensively discussed, we suggest distinguishing between two kinds of social affordances – those that, when positively valenced, promote doing things together (joint action) and those that promote living together. In other words, we assume that there is a spectrum of social affordances, ranging from weak instances to full-fledged forms of social affordances, that presuppose that both agents belong to a social community and may eventually exclude the smart machines we know nowadays.

A paradigm case of doing things together includes telic joint activities, such as painting a house together, whereas living together implicates the atelic activities of friendship, family life, civic or political community, or even those who would comprise the kingdom of ends. Living together is partially constituted by repeated instances of doing things together but is irreducible to these telic activities.

Having distinguished paradigm cases of environmental affordances and two varieties of social affordances, we discuss two questions focusing on the human-machine relation and the machine-human relation, respectively:

1. To what extent can smart machines not only take on the role of environmental affordances but also function as social affordances for us?

2. To what extent can human counterparts play the role of environmental and social affordances for smart machines?

There is no question that the design of smart machines invites us to specific actions. However, acknowledging the increase of agentive properties as well as linguistic and other socio-cognitive abilities smart machines possess, we argue that there are cases where machines – even though they are just objects – take over the role of a social affordance for us humans. This is especially the case when machines use linguistic abilities like all the versions of LLM-based chatbots. They seem to invite us to play all kinds of language games for which we automatically presuppose that our interlocutors are a kind of social agent. At this point, one could still argue that this is a category mistake, claiming that we should refrain from anthropomorphizing machines.

Applying the distinction between telic social affordances and atelic ones, we will present examples of HMIs for which one can explain the behavior of smart machines by the claim that they are taking us for telic social affordances. To this end, we refer to asymmetric joint actions that allow the two interaction partners to fulfill distinct conditions. A positive answer to the second question paves the way to also come to a positive answer concerning the first question. By assuming some sort of reciprocity, it becomes at least questionable whether our stance towards smart machines as social affordances should be categorized as a category mistake.

3. Şerife Tekin & Liz Bowen: Therapeutic Illusions: Self-Knowledge and Empathy in AI Psychotherapy

A significant gap exists between the demand for mental health care and the availability of services, particularly among vulnerable populations who are at higher risk for mental health challenges. Some developers and researchers suggest that AI-powered psychotherapy chatbots could help close this gap. These chatbots, which claim to deliver cognitive behavioral therapy via mobile apps, are considered a promising solution due to their affordability, accessibility on smartphones, and availability in multiple language. Although the evidence supporting their efficacy remains limited and contested, AI-powered psychotherapy apps are rapidly gaining traction, a trend further propelled by the FDA’s designation of one such app as a breakthrough device in June 2022 and another for the treatment of depression in April 2024. In this talk I raise epistemic and ethical concerns regarding two assumptions underlying the development of these technologies. The first is what I call the self-awareness assumption, according to which individuals can correctly track their own psychological states—including their beliefs, desires, moods, emotions, responses to triggers, behaviors, etc.—and report them to these AI-powered chatbots expecting to receive help in responding to them. I argue that this assumption is flawed because it overlooks empirical findings on the fragmented, interpretive, and context-dependent nature of human self-awareness and mental state recognition. The second assumption is that AI psychotherapy chatbots have the capacity to make their users to feel as though they are empathized by and cared for. Developers often argue that whether the AI-powered psychotherapy chatbots have agency and empathy matters less than whether the users actually perceive/believe that they do. I articulate ethical concerns regarding the flattening of the concepts of agency and empathy in the deployment of AI therapy chatbots, particularly as it pertains to the principles of humanism in medical care. While generative AI technologies may enhance access to mental health support, they lack the relational and ethical capacities required to serve as true partners in therapeutic encounters.

4. Ellen Fridland: Coregulation and the AI therapist

AI systems are being used more and more frequently in a psychotherapeutic capacity. Before assessing both the potential efficacy and possible pitfalls of non-human systems playing a therapeutic role, it is important to have a robust understanding of the nature of the therapeutic process. In this talk, I examine the importance of the therapeutic relationship in effective psychotherapy, proposing that at least part of what makes the therapeutic relationship important and powerful is the way in which coregulation between therapist and client allows for the transformation of basic affective and attachment schemas. I will provide evidence that coregulation is best understood as an embodied, biocultural phenomenon. As such, coregulation, which is central to the clinical relationship, is a challenge to the possibility of a straightforward non-human replacement to the human psychotherapist. I will go on to offer some open questions that we need to address in order to determine the extent to which imaginative projection by the human client might create the possibility for coregulation and, thus, effective human to non-human coregulation. I will end by forwarding a note of caution about the possible dangers of using human to non-human coregulation as a way to recalibrate attachment systems, especially in immature and vulnerable individuals.

5. Judith Martens: From Social Habit to Social Displacement: AI-Driven Transformation of Our Social Niches

As AI becomes embedded in everyday life, it reshapes the fragile niches in which skilled social interaction is learned and sustained. These systems do more than assist communication—they can erode the slow, embodied work of acquiring ways of being together. What forms of ourselves, and of our cultural evolution, might we be discarding without noticing?

A personal case makes this vivid. After years in a German-speaking environment, I was fluent enough to teach philosophy and write academic work. Yet when a friend told me—in person—that they had lost a close relative, I was speechless. I lacked the practiced, culturally resonant gestures for grief. In a text conversation, I could have asked an LLM to produce a flawless reply. But that ease would bypass the discomfort and effort through which such skills are normally forged—and perhaps unmake them altogether.

If we let AI fill these gaps, we may quietly unlearn capacities that took generations to cultivate. Rather than clinging to past habits or surrendering to AI norms, we should think of (new) practices that protect the awkward, vulnerable spaces where our shared humanity is rehearsed and renewed.

6. Raul Hakli: Social robots as partners in interaction and joint action?

Social interaction takes place between two or more social agents. Human-robot interactions can resemble social interaction, and robots can be programmed to behave similarly to agents acting jointly. Ongoing attempts to extend LLM-type of methods for teaching robots human-like patterns of behavior are expected to have a huge impact on the functioning of future social robots. Robots can already be programmed to recognize human intentions and affordances for joint action, and coordinate their actions with humans, e.g., by simulating team reasoning. However, I argue that there are fundamental differences between robots and proper intentional agents: The lack of authentic motivation deprives robots from autonomy and moral responsibility. This prevents robots from being full participants in human social interactions and partners in joint actions insofar as such actions require capacity to enter normative relations such as social commitments with other agents. If a robot’s behavior is sufficiently sophisticated in its interactions with other agents, it may still be appropriate to attribute social capabilities to it by employing a "social stance", or even a "collective stance", meaning instrumentalist attribution of capacities required by social or joint action, respectively. This is possible while simultaneously holding that robots are not social in the full sense in which humans are social. I will study what this means in terms of our responsibility practices and whether we can assign tasks to robots and trust them to perform their parts even if they are not moral agents that could be trustworthy and responsible for their actions.

7. Phillip Kieval & Cameron Buckner: Artificial empathy, social affordances, and moral development

Increasingly, Large Language Model (LLM) based AI agents are interacting with humans in social ways. Companies are offering chatbots to play the roles of tutors, advocates, advisors, companions, counselors, romantic partners, and proxies for deceased loved ones. Efforts are already underway to make these chatbots more socially satisfying by endowing them with more empathetic responses to user prompts. For example, if a user says that they just lost their job, then the chatbot should predict that this provokes an emotional response in the user and respond with a message that acknowledges that emotion in some way that the human finds appropriate (as opposed to a merely callous response, such as citing unemployment statistics). Lost in these efforts is the idea empathetic engagement in social interactions are opportunities not just for predicting and responding to emotionally-laden information, but as affordances for moral development. Sentimentalist moral philosophy has long theorized that moral maturation involves the cultivation of virtuous emotional responses and habits through empathetic calibration with other agents. If we treat artificial empathy merely as a problem of creating a more satisfying chatbot, we face the danger of offering users “social junk food” that may be satisfying to users in the short term, but lead to longer-term consequences to mental health and moral development. On a longer term horizon, we also forgo the possibility that creating more subtle forms of empathetic engagement by AIs will allow the bots themselves to achieve more mature forms of moral decision-making. Instead, this paper argues, AI should here take guidance from sentimentalist moral philosophy in the cultivation of artificial empathy, understanding empathetic interactions as affordances for moral development.

8. Kirk Ludwig: Social Affordances and Large Language Models

An affordance is a property of an agent’s environment that offers or allows the agent the opportunity for a certain kind of action, such as a knob or a switch, a break in a hedge, a doorway, or a path worn in the grass across a quad. The perceptual encoding of action affordances facilitates efficient pursuit of goals and is an important component in skill development.

Social affordances present action opportunities for the expression of social action. Not all social action involves joint action, but joint action is a central case and will be my focus here. Social-action affordances are typically learned. An extended hand is an offer to shake hands in greeting or in agreement but as a convention it must be learned. Similarly, an experienced quarterback may see the position of a defense back as an affordance to complete a pass on a slant route. Social affordances are presented not only for individuals but also for groups when the affordance is for a joint action. An infield ball to the shortstop, with a runner on first, may be seen by the fielding team as an affordance for a double-play.

In this paper, I aim to do two things. The first is to develop a theory and taxonomy of social affordances—for individuals, for groups, for institutions, and for individuals in institutional contexts—and their practical and ethical implications. The second is to consider the practical, psychological and ethical import of LLMs—such as Open AI’s ChatGPT and Google’s Gemini, among others—designed to provide social cues, that is, to mimic in one way or another social action affordances. See Google’s television ad for Gemini, for example, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mNTGbi5ReMc, as well as the flood of “companion” apps available for phones, tablets, and computers, such as friend bots, therapy bots, girlfriend/boyfriend bots, and love bots. Examples are AI girlfriend, Anima, Digit, Guru, Pheon, Replika, Romantic AI and the like. Top.AItools lists over seventy girlfriend bots and seventy therapy bots alone. The rapidly developing work on integrating LLMs with robotics will lead to the addition of multimodal cues for social interaction. I will argue that LLMs only provide pseudo-social-affordances. Then I will argue that when designed to take in users they invite a form of trust and the adoption of a psychological stance that is misdirected, in consequence of which the forms of interaction that are attempted cannot be satisfied. This represents, I will argue, a form of trust betrayal, a denial of value, and a loss of opportunity akin to being catfished. The blame lies not with LLMs, which are not agents, but with their corporate sponsors. The cat(fish) is out of the bag, and we cannot put it back in. However, I end with some policy recommendations designed to mitigate harms of artificial signaling of social affordances when no such opportunities exist. In particular, I will argue that every effort should be made to encourage conceptualizing LLMs as tools rather than potential social partners.

9. Amber Ross:

tba

Short description OF THE WORKSHOP

With the unexpected progress in generative AI technology, we may find ourselves at the beginning of an AI revolution. Artificial systems will increasingly play a role in our social world. To understand their impact, this workshop proposes to combine foundational work from philosophy on the nature of joint skilled action, including the role of affordances, with the analysis of interactive AI systems, which have the potential to qualify as potential partners in social agency.

Many skills essential for us as social agents can only be expressed with others or involve others as social objects. Utilizing the concept of ‘affordances’ by which properties of an agent’s environment are described, properties that offer or allow an opportunity for a particular kind of action, one can frame a notion of social affordances that includes properties of the other social agents presenting action opportunities for the expression of social action.

Similarly to human-human interactions, we may observe social affordances in human-machine interactions: AI systems such as LLMs and social robots are designed to provide social cues and thereby offer action opportunities for the expression of social action.

This leads to a wide range of theoretical, practical, and ethical questions that arise about artificial systems producing social cues. Among these are:

- What are the commonalities and differences between human-human, human-machine, and machine-machine interactions?

- What is missing in interactions in which machines are involved in comparison with human social interactions?

- What are the practical and ethical implications?

- Can (and if so, should) artificial systems be trained to be skilled “partners” in joint activities with human partners?

- Can artificial systems based on generative AI technology (like LLMs) qualify as genuine agents and, in particular, social agents?

- To what extent do they genuinely present social affordances? To what extent do they have social skills?

- How should we conceptualize the abilities of artificial systems that may play roles in joint intentional activities? Does it make a difference whether the human agent conceptualizes the AI system as a tool as opposed to a partner in a joint activity?

detailed workshop description

long description

This workshop seeks to bring together two topics. The first is the nature of joint skilled action and socially skilled action more generally, and how this informs and is informed by social affordances. The second is how these skills and capacities for recognizing social affordances interface with new and potential future developments in AI systems, especially Large Language Models (LLMs) and other deep neural networks (DNNs) with interfaces that at least mimic social interactions such as conversations.

Traditional work on skill action has focused on individual agents engaging in activities that they can carry out by themselves or, when a joint action is involved, the focus has been on the individual contribution in isolation rather than what the group does. But many skills essential for us as social agents can only be expressed with others or involve others as social objects essentially. For example, in pairs figure skating, the skills of each of the partners cannot be practiced or expressed except in the context of their acting together. Even in competitive games like table tennis, the practice and expression of the skills takes place only in the context of joint action. Skills with social objects include psychotherapy, mediation, marriage counseling, negotiation, medical care, institutional design, legislation and so on. In addition, many skills that are socially significant are skills exercised not by individuals but groups. Teams with players of equal ability may differ in their group skills because of team chemistry, an amalgam of complementary skills, trust, mutual understanding, shared commitment, know-how, communication, mutual responsiveness, and knowledge of individual members of their roles in team play, among other things. In social skills there is a role for both automatic action and control, which have traditionally been opposed views in theorizing about the basis of skills. The importance of understanding group skilled action can’t be overemphasized. Group can do things that no single individual can do. Much of social reality, the infrastructure of civilization, and institutional knowledge production, as in the practice of science relies on skilled group action.

In the broad sense, an affordance is a property of an agent’s environment (broadly construed) that offers or allows the agent the opportunity for a particular kind of action, such as a handle or knob, a break in a hedge, a doorway, or a path worn in the grass across the quad. The perceptual encoding of action affordances can facilitate efficient pursuit of goals and is an important component in skill development and expression. An affordance, for an agent, in the narrow sense, is an affordance in the broad sense that is apparent to the agent. If it is perceptually encoded, we may say that it is perceptually apparent to the agent. Good design aims, inter alia, at presenting affordances that are perceptually apparent to an agent.

Social affordances (in the broad and narrow senses) present action opportunities for the expression of social action. Social affordances and social skills go hand in hand. Social perceptual affordances are typically learned. An extended hand is an offer to shake hands in greeting. But it is a learned convention that we greet each other by shaking hands. Similarly, a quarterback may see in the position of a defensive back and his running back an affordance for a completed pass on a slant route. Social affordances are presented not only at the level of individuals potentially engaging in joint action but also at the level of groups. A team of researchers may see in advances in mRNA manipulation the affordance for novel and faster routes to vaccine production. A corporation may see in the development of LLMs an opportunity to increase efficiency and reduce costs in customer service.

This brings us to our second, interconnected, topic: social affordances at the human-AI interface. AI systems are tools. Tools are designed for certain functions. They present affordances for the functions for which they are designed. But most tools, from hammers and screwdrivers to cars and pocket calculators, do not present social affordances but rather affordances for individual goal-oriented behaviors. AI systems such as LLMs and social robots, in contrast, are designed to provide social cues. For example, LLMs such as ChatGPT are interactive systems that respond in real time to prompts from human agents with text output that cannot reliably be distinguished, except for the speed with which it is produced, from intelligent human agents. There is a wide range of theoretical, practical, and ethical questions that arise about artificial systems producing social cues. Among these are:

• To what extent do LLMs and social robots (especially ones which potentially integrate LLMs and complementary deep neural networks) genuinely present social affordances? To what extent do they have social skills? The answer to this question raises questions about whether LLMs or LLMs equipped with “perceptual” transducers and motor outputs are or could be genuine agents and in particular social agents. What is the threshold required if it is possible at all?

• How should we understand the psychology of human AI interfaces when AI systems can mimic social activities? Does it make a difference whether the human agent conceptualizes the AI system as a tool as opposed to a partner in a joint activity?

• What is missing in these interactions in comparison with human social interactions? What are the practical and ethical implications?

• To what extent can AI systems be recruited to play (in some sense of ‘play’) roles in joint intentional activities and how should we conceptualize it?

• What are the implications of enlisting AI systems in decision making or management roles vis-à-vis teams of human agents?

• Can (and if so, should) LLMs be trained to be skilled “partners” in joint activities with human partners?

• Are there potential advantages to training teams of AI systems to emulate joint problem solving, especially in the case of interlocking complementary skills? What should the role of human supervisors be in this case?

• What are the commonalities and differences between human-human, human-machine, and machine-machine interactions?

• What are the theoretical and normative implications of our lack of an analytical understanding of how DNNs accomplish the tasks set them?

In sum, we are at the beginning of an AI revolution. To understand its impact on the social world, the workshop proposes to combine foundational work on social skills and affordances with a look at their interface with interactive AI systems and assess AI systems as potential partners in social agency.